Real Kindness

Is Criticism

From an

Aesthetic Realism Public

Seminar

by

Lynette Abel

At age twenty,

if someone

had asked me if I wanted to be kind, I certainly would have said yes,

but

I didn't feel I was kind. Though I could go out of my way to help

a friend, I essentially felt I was selfish and cold to people--my

college

roommates, my family, the men I knew. I was longing to know, what

I have learned from Aesthetic Realism: that real kindness is a critical

and intellectual achievement that makes for the happiness and

self-respect

we are hoping to have. In his great work Definitions, and

Comment:

Being a Description of the World, Eli Siegel explains:

"Kindness is that in a self

which wants other

things to be rightly pleased....To be kind is honestly to think of what

another person, or other persons, truly desire. If we do not take

the trouble to find this out, or do not want to take the trouble, our

"kindness

is so much not kindness. Kindness is accuracy...."

Aesthetic Realism teaches

that every person's deepest desire is to like the world. And in

order

to be kind, I learned, we have to be critical, to want to know and be

for

what will strengthen a person's like of the world and be against that

which

weakens every person most, the desire for contempt, "the lessening of

what

is different from oneself as a means of self-increase as one sees

it."

The greatest kindness came to me from Eli Siegel and Realism: when I

heard

exact criticism of my contempt, my life began anew. I was able to

see people and things, at last, in a way I could be proud of.

The Mix-up about Kindness

Begins Early

Growing up,

in Alexandria, Virginia, I came to have the customary notion of

kindness

as doing nice things, like offering to wash the dishes or lending a

skirt

to my sister. I equated kindness, as many people do, with getting

praise and giving it.

And I used

my family’s praise to feel I was special and I had a right to look down

on other people.

I remember

many times driving through an area called Gum Springs on my way to

downtown

Alexandria. The people who lived there were very poor and their

houses

were dilapidated shacks, many with broken windows and some without

doors.

I remember thinking scornfully about them: I was callous to the depths

of other people, whom I saw as so different from myself. That

people,

fellow human beings, had to endure these deplorable conditions is

shameful!

The fact is, that they were forced to, as people are today, because of

an unjust, brutally unkind economic system which allows only some

people

to live comfortably while others live in abject poverty. And I

needed

so much to know what Eli Siegel explains in his lecture Mind and

Kindness:

"Deep in the meaning of the

word kind is

a feeling that through being born there is a relation to everything

which

is also born or existing....Any person who isn't kind, in the real

sense

of the word, is a person who is hurting himself. I mean by kind,

a proper awareness of all things that are in any way like you."

I did not have "a proper

awareness" of the feelings

of people--my friends, men I knew, my family. And I didn't know

that

my unkindness was the reason I felt painfully nervous around just about

everyone.

At Florida

State University, I studied English literature and sociology, but I

also

was after glory for myself and wanted to forget about the world.

This took in how I saw men. Like my family, I saw men as existing

for the purpose of praising and making me important. When my

boyfriend,

Tom Welsh, was drafted during the Vietnam war, and stationed in the

Pacific

Islands, though we had discussed marriage, he wanted to wait until he

got

back. Instead of being interested in what, for instance, he felt,

and how I could encourage him, I was hurt and felt I had a right to be

unkind. So while I wrote him praising letters, telling him how

much

I loved and missed him, all along I was dating other men. But as

I went after what I saw as the most glorious thing--having a number of

men interested in me at once, I disliked myself intensely. I felt

agitated and my thoughts were so distracted that I couldn't concentrate

on my studies.

One

day I received

a flattering poem from Tom titled "To the Woman I Love," which began:

"I

love a beautiful woman, a woman who loves,” and ended, "The woman I

love

is complete...." Though this was what I thought I wanted to hear

most from a man, after I read it, I felt awful. I knew it wasn't

really me he was describing, and I thought he was foolish. What I

was desperate for was not utter praise, but accurate criticism of where

I was unjust. I met this some years later in Aesthetic

Realism.

We Are Looking for

Criticism

For example,

in a class Mr. Siegel explained centrally what had caused me so much

pain:

"You can participate in something while not believing in it--isn't that

a description of your life, Miss Abel?" It was. In another

class, he asked me: "Do you think your chief hurt in life comes from

having

two motives: justice and glorification?" "Yes" I replied.

He

said: "Justice should always win over glorification, because

glorification

is a garbage can....You will never feel good unless you feel kindness

and

good will are good sense."

I thank

Eli Siegel and Aesthetic Realism for enabling me to change from an

uninterested,

self-absorbed person, to a person who now sees wanting to know

and

strengthen other people, including my husband, Michael Palmer, as a

kind

necessity and pleasure.

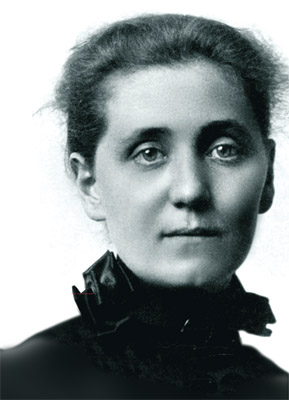

Jane Addams' Life

Shows Real Kindness

Is Criticism

Eli Siegel

defined kindness as: "that in a self which wants other things to be

rightly

pleased." And in the comment to it, he explains: "A person is

kind

who feels a sense of likeness to other things; who accepts accurately

his

relation to other things." These sentences comment deeply on what

impelled

the important American social reformer, Jane Addams, who lived from

1860-1935.

She showed in a big way, from which every person can learn, that we are

kind when we are critical of injustice wherever it is. In 1889,

with

Ellen Starr, she founded Hull House, in Chicago's West Side slums, one

of the first social settlements in the United States. She felt

there

were basic necessities every person deserved to have, and it was her

obligation

to have people get them. "It is natural to feed the hungry and

care

for the sick," she wrote of her purpose. "It is certainly natural to

give

pleasure to the young, [and] comfort the aged...." Jane Addams

saw

the feelings of immigrant workers as real--something many people did

not--how

their lives were being brutally exploited for profit in Chicago's

factories.

Jane

Addams was born

in 1860 in Cedarville, Illinois, the eighth child of Sarah and John

Addams.

When she was two years old, her mother died, after giving birth to her

ninth child. Her father, who was a member of the state senate,

was

a friend of Abraham Lincoln and was himself a fervent

abolitionist.

He remarried when Jane was seven. Their family was well-off and

Jane

had many advantages other children didn't. In her autobiography,

Twenty Years at Hull-House, she tells of being shocked when, as a

little girl, she saw "horrid little houses" in a neighboring

town.

Unlike how I wanted to feel superior to people, when Jane saw the

hideous

conditions in which some persons were forced to live, she was critical

and asked, "what could be done to make them less horrid?" She

wanted

them "to be rightly pleased." Jane

Addams was born

in 1860 in Cedarville, Illinois, the eighth child of Sarah and John

Addams.

When she was two years old, her mother died, after giving birth to her

ninth child. Her father, who was a member of the state senate,

was

a friend of Abraham Lincoln and was himself a fervent

abolitionist.

He remarried when Jane was seven. Their family was well-off and

Jane

had many advantages other children didn't. In her autobiography,

Twenty Years at Hull-House, she tells of being shocked when, as a

little girl, she saw "horrid little houses" in a neighboring

town.

Unlike how I wanted to feel superior to people, when Jane saw the

hideous

conditions in which some persons were forced to live, she was critical

and asked, "what could be done to make them less horrid?" She

wanted

them "to be rightly pleased."

We Need Criticism to Be

Kind

In

her autobiography, Jane Addams tells of something that had a big effect

on her whole life. When she was 11, Jane came into her father's

room

and found him looking very solemn. He told her that Joseph

Mazzini,

the great Italian patriot, was dead. She grew argumentative,

asserting

that he didn't know Mazzini, and that Mazzini was not American, so why

should we feel so bad? Her father was critical, and told her that

the feelings of people in another country had very much to do with the

feelings of people in Illinois--just as there were "...men who are

trying

to abolish slavery in America," there were men trying to "throw off

Hapsburg

oppression in Italy." She saw, she later wrote--though people may

"differ in nationality, language, and creed," they "shared large hopes

and like desires." She said, "I came out of the room

exhilarated."

Jane Addams

graduated valedictorian from Rockford Seminary in 1881. As she

thought

about what she wanted to do with her life, she traveled throughout

Europe

for a number of years in what she described as a "feverish search after

culture." But she didn't want, she said, just an "intellectual"

life.

She was in a fight between the desire to be useful to people and a

certain

selfishness which she described as "a continued idleness...[a] going on

indefinitely with study and travel." Then one day, as a tourist,

she witnessed in London, a Saturday night auction of decaying

vegetables

and fruit to poor people and it changed her life. She wrote:

"We saw two huge

masses of ill-clad

people clamoring around two hucksters' carts. They were bidding

their

farthings and ha'pennies for a vegetable held up by the

auctioneer,...one

man...had [bid for] a cabbage, and when it struck his hand, he

instantly...tore

it with his teeth, devoured it, unwashed ...as it was....[T]he

impression

was...of myriads of hands, empty, pathetic, nerveless and

workworn,...clutching

forward for food which was already unfit to eat. I have never

since

been able to see a number of hands held upward, even when they are

moving

rhythmically in a calisthenic exercise, or when they belong to a class

of chubby children who wave them in eager response to a teacher's

query,

without...this memory, a clutching at the heart reminiscent of the

despair

and resentment which seized me then."

That

people had to depend

for their sustenance on decaying food enraged Jane Addams and she felt

an obligation to do something about it. In September of 1889, she

obtained a house on Halsted Street, in the slums of Chicago, and Hull

House

opened. In his great lecture, "Aesthetic Realism Looks at Things:

Seeing and Grabbing," Eli Siegel explains:

"Out of the feeling that owning

has been disproportionate...has

arisen the settlement movement,... Jane Addams...said that people were

dealt

with unjustly in terms of what they have and what other people have

grabbed."

Jane

Addams wanted

to bring comfort to persons who were poor, but more than that she

wanted

to get rid of poverty. Two important women, who worked with her

at

Hull House, were Florence Kelley, who did extensive investigation into

the horrible conditions of the sweatshops, and Dr. Alice Hamilton, who

became the foremost authority on work-related illnesses.

The

Chicago of 1889

was teeming with industry--meat-packing, banking, manufacturing; (it

isn't

today, but not different from today) there was vast wealth and vast

poverty.

Men and women worked 7 days a week, 12-14 hours a day, for wages they

couldn't

live on, and even little children worked long days for four cents an

hour.

The surrounding neighborhood was described by a Hull-House

investigator:

"...[L]ittle idea can be

given of the

filthy...tenements... and dilapidated outhouses, the piles of garbage

fairly

alive with diseased odors, and the numbers of children filling every

nook,

working and playing in every room,...pouring in and out of every

door...."

Hull-House

provided a day nursery and kindergarten to care for children of working

mothers, a public kitchen, an employment bureau, and cooperative

housing

for young working girls. A Theatre was begun and a music

school.

"In the first year, 50,000 people came to the house," Biographer James

Weber Linn wrote: "and it is no exaggeration to say that Jane Addams

talked

to most of them."

In his comment to the

Definition of

Kindness, Mr. Siegel writes:

"If [a person] has

the organic feeling

that the being pleased of other things is the being pleased of himself,

he is kind."

This

describes the feeling

Jane Addams had--there wasn't any job she saw as beneath her if it

meant

having people's lives better off. There were disease and death

resulting

from decaying garbage. Garbage collection was not being enforced,

and Jane Addams sent over 1,000 reports of violations of the law to the

health department, and she got the mayor to appoint her Garbage

Inspector.

Every day she was up at 6 am making sure the garbage collectors did

their

work, having to follow the loaded wagons to "their dreary destination

at

the dumps."

In an

Aesthetic Realism

class in 1976, Mr. Siegel spoke about the large meaning of obligation

and

he asked me "Do you have any obligation?" "Yes" I replied.

Eli Siegel.

Do

you think you owe anything to people?

Lynette Abel.

I think I

owe a great deal.

Eli Siegel.

If you were

on the subway and saw a woman ill, would you give her a seat?

Lynette Abel.

Yes....

Eli Siegel.

If you can

make anything stronger, would you want to do it? If there were a

smudge on the window would you want to brush it away?

Lynette Abel.

Yes.

Eli Siegel.

Obligation

comes from the desire to have the world better. Obligation is in

the nature of things; something can be better through something you

do.

Good will is a terrific obligation, present with every beat

of one's heart. It is the most beautiful thing in the

world....Every

person has to see obligation as expressing oneself.

Jane Addams felt

she had an obligation to have the world better. When she learned

at the first Christmas party at Hull-House, that a number of little

girls

refused candy, because they had been working 14 hours a day for 6 weeks

in a candy factory and couldn't bear to look at it, she was

shocked.

Then she learned of a boy who died in a factory accident which could

have

been prevented by a machine-guard costing a few dollars. Jane

Addams

wrote:

"We felt quite sure

that the owners

of the factory would share our horror and remorse, and that they would

do everything possible to prevent the recurrence of such a

tragedy.

To our surprise they did nothing whatever."

But Jane Addams did.

Through her work and

that of others, on July 1, 1903 the Illinois child-labor laws were

passed.

Relating Jane Addams' desire to uncover evil to the novelist Henry

James,

in the preface to James and the Children Mr. Siegel

writes:

"[Henry] James makes

the unseen less

unseen. Here he is with St. Francis, William Godwin,

Christ,

John Brown, William Cobbett, Jane Addams."

"Kindness Is Accuracy."

With all of

Jane Addams' kindness and usefulness, there was something big she did

not

see at the time of an important occurrance in the history of labor--the

Pullman Strike of 1894. George M. Pullman, owner of the Pullman

Palace

Car Company, built a town for his employees which they had to live

in.

Rents and services were exorbitant and biographer Allen Davis, writes

"most

of the apartments had no bathtub, [and] there was only one water faucet

for every 5 units." Seeing the lives and work of people as a

means

of making profit for oneself, I learned from Aesthetic Realism, is

hideous,

unkind contempt. When in 1893, Pullman laid off a number of

employees

and cut the wages of those who remained, the workers were forced to go

out on strike. They appealed to the American Railway Union, newly

organized by Eugene V. Debs for support, and got it. The boycott

of Pullman cars brought the entire national rail system to a

standstill.

Florence Kelley and Ellen Starr were out on the picket

lines.

President Cleveland sent in federal troops to break the strike.

34

people were killed, and over 700 were arrested, including Debs.

Jane Addams

did not want to see clearly, unequivocally that Pullman was unjust, but

instead referred to him as a "benevolent employer" and argued "there

was

blame on both sides...labor and management needed...to learn [to] work

together." She, like other social reformers, didn't see--what

only

Aesthetic Realism explains--that it was contempt which made for profit

economics and its horrible effects, and that this same contempt is in

every

self and needs to be criticized. In his lecture on Aesthetic

Realism

Looks at Things: Seeing and Grabbing, Eli Siegel explained "[The

Settlement

movement] was a way of admitting injustice, but not admitting it too

strongly."

In the late 19th century Jane Addams underestimated contempt; she was

wrong

in thinking employers could ever be fair to workers, while wanting to

make

a profit from them.

However, as

years went on, her interest "in what people deserve" became stronger,

not

weaker and extended out from Hull-House nationally and

internationally.

In 1912, Jane Addams seconded Theodore Roosevelt's presidential

nomination

at the Progressive party convention. "The Progressive Platform"

she

said "contains all the things I have been fighting for." In her

speech

she said:

"A great party has

pledged itself

to the protection of children, to the care of the aged, to the relief

of

overworked girls, to the safeguarding of burdened men."

In his

historic lecture

of June 12, 1970 called "What Is Working Now?" published in Goodbye

Profit System: Update Eli Siegel discusses the Progressive Party

platform,

placing its important ethical value. He explains:

"[T]he reason the

platform came to

be is the desire to have good will as power....It is part of this

century's

history, and it has gone to make what we have now: the inability of the

profit system to function the way it would like."

To

her credit

Jane Addams, felt she needed to do better. At a large dinner in

Chicago

in 1927, when many speeches were given praising her for "her age-long

quest

for self-respect" and "a better and kindlier world," she replied

self-critically:

"I am very grateful

for the affection

and interest you have brought here this evening; yet in a way

humiliated

by what you say I am, for I know myself to be a very simple person, not

at all sure I am right, and most of the time not right, though wanting

to be; ...I can only hope that we may go on together, working...for the

betterment of things,..."

In

an Aesthetic

Realism lesson of 1969 Eli Siegel spoke of what people are hoping

for.

I conclude my paper with these sentences from it:

"The need for

criticism, that is,

asking the world please world tell me where I'm incomplete is as fierce

as the desire for milk....In the full sense of the word the self is

comfortable

in two ways: 1) It should have food and heat enough, the other is that

its path seem to be fitting. For instance, let's say a person is

told "Look, you're on the wrong road now. That is the one you

want

to take." He had a notion before it might be the wrong road but

once

he's sure, he is more comfortable....Criticism and kindness are the

same

thing completely."

|